[ad_1]

Respiratory diseases in captive reptiles are all too common unfortunately and are a great source of frustration for owners and vets alike, as well as being a serious welfare concern for the animals affected. There are many causes including parasitic, bacterial, viral and fungal infections as well as traumatic injury, tumours and cardiac disease. Reptile respiratory disease is often more severe and difficult to treat than in mammals due to differences in anatomy and physiology, outlined below. As a vet with a special interest in reptiles, I often look at online herpetological forums. Treatment of respiratory infections, or R.I’s, is one of the most frequent topics provoking debate and disagreements, prompting criticism of vets as well as hobbyists, and often resulting in potentially harmful or at least misleading information being spread by so called experts. I am writing this article to provide an overview on respiratory conditions and treatments in reptiles. Hopefully this will give a better understanding of how such conditions can be prevented, what to look for when they do occur, how they can be treated and why they can be so difficult to treat. I will also attempt to dispel any misconceptions and answer some of the most common questions I encounter in clinical practice as well as on hobbyist forums. Similarly I will try to explain the decision making process and give an insight from the vet’s side of the consult table as I do see this as an area where the vet-client relationship is frequently strained due to poor communication on both sides.

By far the best advice I can give as a vet is in prevention of respiratory disease through various husbandry and biosecurity measures. I would also like to highlight why specific advice given by experienced reptile veterinarians is so important in the outcome of the case. I have often been disappointed and disheartened in practice when treating an R.I. case when the owner doesn’t follow the directions given or take my husbandry advice on board, and is then disappointed when the treatment fails or they can no longer afford treatment and the animal ends up severely debilitated, has to be euthanised or dies. I have had my work and reputation criticised to colleagues and undoubtedly on forums when “the antibiotics he dispensed didn’t work”. These were invariably in cases where the owner didn’t follow all the other suggestions that go along with medication, when they brought the animal to me in an advanced state of disease and were informed of a guarded prognosis but decided to try treatment anyway or where they didn’t return for me to establish why my treatment of choice didn’t work. I will get the defensive vet disclaimer out of the way now at the start of the article. Treating R.I’s in reptiles is not just about dispensing antibiotics, or about which antibiotic is dispensed. Enough with the Baytril bashing! Successful outcomes rely on a holistic, integrated approach as well as the hobbyist working with the vet, not against. Believe it or not, and I can’t speak for every vet, our main concern is that your animal gets better and we have a happy client at the end of our interaction. With that said, let’s get on with our discussion…

Anatomy & Physiology:

The difficulty in treating respiratory disease in reptiles is primarily due to their inability to effectively clear fluid, debris and discharges from their airway by coughing. Most species, apart from crocodilians, lack a true diaphragm and therefore do not possess a cough reflex. The mucociliary escalator apparatus is poorly developed in the reptile airway also, which complicates clearance of infectious agents and subsequent secretions. The mucociliary escalator is an adaptation of mammals which allows any inhaled debris, micro-organisms or secretions to be transported up the airway and trachea (windpipe) by mucus and tiny microscopic hairlike projections, clearing them from the airway and allowing them to be swallowed into the hostile acid environment of the stomach. This is a vital defence against respiratory infection and disease which is lacking in reptiles when compared to mammalian species.

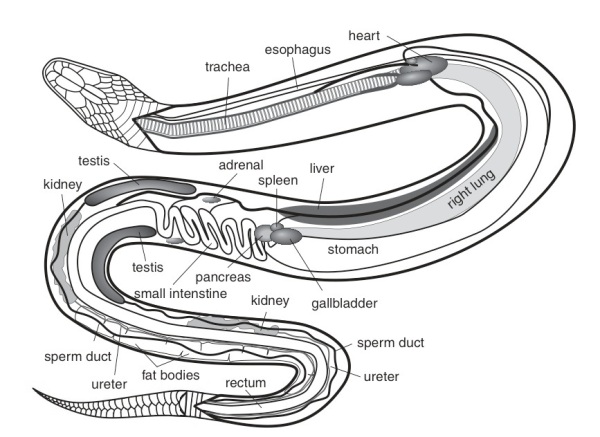

Secretions and infectious material therefore pool in the lower parts of the lungs making penetration by immune cells as well as medications very difficult, leading to chronic disease which is often difficult to treat. So having the same expectations for treatment of a respiratory infection in a snake or lizard for example compared to a dog or cat may result in disappointment. The anatomy of the reptile respiratory tract is also unique in several ways which can affect disease progression. The main anatomical feature of significance in reptiles is in snakes, most of which only have a single right lung. Lizards and chelonians have two symmetrical lungs. Boas and Pythons have a main single right lung and a much reduced or vestigial left lung. Some snakes also have a ‘tracheal lung’ which is an outpouching of the trachea with respiratory mucosa for gas exchange. Because of the single lung, snakes with respiratory infections are therefore even more challenging clinical cases than chelonians and lizards.

Causes:

Poor husbandry is the single most important factor predisposing captive reptiles to disease, respiratory or otherwise. It should not be necessary to mention that the specific and exact needs of the individual species kept need to be researched and met accurately in order to preserve health and prevent health problems. Respiratory infections (R.I.’s) in particular, although caused by a variety of different pathogens, can almost always be traced back to an incorrect or inadequate husbandry issue, most notably related to temperature and humidity. It is therefore of the utmost importance that all reptiles are provided with perfect husbandry conditions that mimic as closely as possible their natural conditions and requirements in the wild. If any husbandry issues are sub optimal then the animal may succumb to an opportunistic infection through gradual debilitation and weakened immune defences. Nutritional deficiencies are a common factor leading to such debilitation and subsequent predisposition to infection. Hypovitaminosis A is important to mention as a lack of this vitamin frequently leads to disease or the oral and respiratory mucosa and therefore has a big impact on respiratory health. With this in mind let’s now discuss the various causes of respiratory illness.

Parasites:

Most common parasitic infections affecting the respiratory tract are caused by nematodes including Rhabdias spp. in snakes and Entomelas spp. in lizards. These are specialised lungworms, although other nematodes can cause respiratory illness such as Kalicephalus spp., the snake hookworm which migrates through the body after entering via the skin or by ingestion, potentially causing severe tissue inflammation as it passes through tissues on its journey to the gut. Similarly, ascarid worms frequently cause damage to lung tissue and the liver as they pass through the body as migrating larvae. Apart from nematodes, the single-celled parasite Entamoebas invadens has been found to cause respiratory illness on occasion as well as some evidence of coccidiosis affecting the lungs in chelonia. In amphibians, particularly wild caught specimens, the lungworm Cosmocercoides spp (see my image below from a White’s tree frog) can be found relatively frequently and is often fatal especially in captivity stressed or debilitated individuals (more information at: http://www.matthewbolek.com/research/nematodesindex.html).

Bacteria:

Many bacterial pathogens have been isolated and implicated in lung disease in reptiles, some of which are primary pathogens and others are secondary invaders causing opportunistic infection. The presence of these micro-organisms does not necessarily indicate that disease is present, as they may be opportunistic only causing disease when the animal’s immune defences are weakened or defective. Further pathogens may extend into the respiratory tract from other sites, most notably from generalised systemic infection or septicaemia, or from mouth infections (stomatitis). The primary bacterial pathogens responsible for R.I.’s in reptiles most commonly are Aeromonas spp., Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp., Salmonella spp. and Pasteurella spp. Bacterial infections may go hand in hand with viral infections, a common example being Mycoplasma or Mycobacteria present alongside Herpesvirus infection causing rhinitis or ‘Runny Nose Syndrome’ in tortoises. Finally, Chlamydophila spp. has been implicated in some pneumonia in snakes.

Fungi:

Fungal R.I.’s are less common than bacterial or viral disease but do occur, most frequently in chelonians such as tortoises. The commonest infections result from exposure to saprophytic or soil fungi in the external environment and most are secondary pathogens to bacterial disease or traumatic injuries. If husbandry is inappropriate particularly with regard to ventilation and humidity the risk of fungal disease is often increased. Notable species of fungi causing such infection are Aspergillus, Candida, Sporotrichum, Penicillium, Paecilomyces and Cladosporum spp.

Viruses:

Several viral diseases are responsible for respiratory disease in reptiles including Paramyxovirus, IBD, Herpesvirus and Iridovirus.

Ophidian Paramyxovirus (oPMV) is becoming increasingly common in captive snakes, and has been occasionally reported in lizards, though these are frequently asymptomatic when infected. This virus is highly infectious causing haemorrhagic pneumonia and viraemia affecting other organ systems. It is shed in respiratory secretions and can be easily spread through a collection by poor hygiene and sanitation practices. Animals may lack clinical signs for long periods with the incubation phase lasting up to 8 weeks, so testing during this period can turn up false negative results for this reason. Testing usually relies on post mortem sampling but blood serum analysis can be performed. Another paramyxovirus related to the parainfluenza 2 virus (PI2) has been implicated in respiratory disease as well.

Inclusion Body Disease (IBD) is a viral infection primarily of boas and pythons which can causes respiratory disease in the form of pneumonia, in addition to the more common central nervous signs such as ‘stargazing’ and gastrointestinal disease causing regurgitation and anorexia. The exact viral agent responsible for IBD has long been debated and researched. Thought to be a retrovirus scientists have only recently discovered that the infection is in fact caused by a new virus belonging to the Arenavirus group.

Herpesvirus is a common cause of respiratory disease in chelonians, particularly Mediterranean tortoises, often with devastating consequences. Such infections often cause secondary bacterial and mixed viral infections. Clinical signs include lethargy, rhinitis or ‘runny nose’, anorexia, conjunctivitis and stomatitis. This is a complex and extensive topic in itself, therefore I will endeavour to write a future article on the subject.

Finally, Iridoviral infections with Ranavirus in particular from amphibian hosts can cause severe necrotising tracheitis and pneumonia. This is an extremely aggressive infection causing extensive and painful tissue damage. Infections are extremely difficult to treat.

Trauma:

Trauma to the carapace of chelonians can lead to non infectious lung disease, often associated with attacks by dogs or wildlife, car accidents and even lawnmower injuries! Shell repair techniques are undertaken according to the individual injuries, but treatment of shock and secondary infections is vital in order for a successful outcome.

Tumours:

Cancer as in most species occurs more commonly in older animals, and is normally diagnosed by X-ray of the lower respiratory tract. Treatment is experimental as chemotherapy in reptiles is not widely used or researched.

Foreign Bodies:

Inhaled foreign bodies are possible, but not common. Endoscopy is a useful tool for removal.

Cardiac Disease:

Congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathies occasionally are seen, primarily in older or geriatric reptiles and can cause fluid congestion in the lungs leading to increased respiratory effort and subsequent lung disease. For an article on these conditions in two cases I saw in practice, visit https://exoticpetvetblog.wordpress.com/2014/07/11/124/.

Clinical Signs:

Signs of disease are often very similar irrespective of cause, but can be extremely subtle particularly in the early stages of disease. The ability of reptiles to mask any signs of illness and the chronic nature of disease progression mean that by the time an owner notices the animal is unwell, the disease is already advanced. Again this has implications for successful treatment, so if in doubt or any of the following signs are observed, you should seek treatment immediately:

- Dyspnoea (difficulty breathing) which can manifest as increased respiratory effort, extension of the neck or gulping for air

- Tachypnoea (increased respiratory rate/rapid breathing)

- Open mouth breathing

- Yawning (particularly in snakes)

- Nasal or oral discharges (appearance depends on cause; blocked nostrils may indicate previous discharge)

- Ocular (eye) discharge

- Respiratory noises (clicks, wheezes, ‘snuffles’)

- Lethargy/depression

- Anorexia/reduced appetite

- Altered buoyancy in aquatic species

- Dehydration

- Postural changes (elevating head and neck vertically, particularly in snakes)

- Altered thermoregulation (seeking cooler areas to hide, to alter metabolism and cope with hypoxia or diminished blood supply of oxygen)

- Concurrent infections, specifically stomatitis or ‘mouth-rot’

Above: Abscess/stomatitis in a Royal Python.

Above: Chronic pneumonia, anorexia, emaciation, stomatitis in a Boa constrictor.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis relies on a detailed history from the owner taking into account the original source of the animal in question, any husbandry issues that might predispose to certain conditions, the range of signs noticed, duration of the illness, species specific considerations, parasite control and nutritional status. Secondly a detailed physical exam will often give me far more information regarding the animal in question than an owner’s description over the phone or photos and descriptions online. A detailed clinical exam is one of the main diagnostic tools a vet has in assessing their patient, which unfortunately cannot communicate directly to us as in human medicine. Observing the animals breathing pattern and effort before handling gives a good idea of functionality and health of the respiratory tract. Examining the mouth and pharynx or throat region will often give clues such as inflammation or discharges from the airway, as well as highlighting stomatitis. Discharges can reveal a lot about the underlying pathogens present and sometimes may be sampled for microbiological examination and culture. Generally, cloudy or yellowish/green discharge indicates bacterial infection but can also be present in fungal or viral disease occasionally. Clear discharges are more classically viral indicators or a sign of mechanical irritation, and rarely seen in bacterial infections. Bloody or blood tinged discharge may indicate a more invasive infection, trauma or damage due to a foreign body in the airway. Similarly tumours of the respiratory tract may occasionally bleed and cause such discharge. Auscultation of the respiratory tract can be challenging in the reptilian patient as movement of rough scales against the diaphragm of the stethoscope can obscure respiratory sounds. Often I will use soaked cloth or cotton wool between the diaphragm and animal to create a better contact and decrease movement noise but this unfortunately also dampens respiratory noises.

As you can see many clues can be gleaned from a clinical examination. This is the reason I and many other vets are reluctant to make a diagnosis without seeing the animal. To do so would be negligent. So even if it sounds like a classic R.I. for example there may be vital signs that the owner relaying the information neglects to disclose, or more subtle signs that haven’t been noticed which alter the diagnosis or indeed prognosis of the case. I would be wary of giving out advice when in fact that advice could be useless or even dangerous to the animal in question. My prognosis may be optimistic if signs of a simple infection are described to me, but if the owner hasn’t noticed more serious signs in a pneumonia case for instance they will be extremely disappointed and doubt my knowledge if their snake dies soon after. Language is extremely important and vets are trained to describe illness in a very specific terminology, which may be completely meaningless to hobbyists. Because of this, one person’s description of a lesion or clinical signs of illness will differ significantly from another’s description. Many times I have had a long discussion with a reluctant owner on the phone to try and assess whether the animal needs to be brought to the vets in the first place, and having asked various questions have a definite picture in my head of the case that will present to me the following day. Quite often there are clues or details omitted or described differently and I am surprised by what is actually presented on the consult table. The point I am making is not to be offended or see my request to book an appointment as a waste of time or a money making exercise, when in fact it is merely that I cannot make a diagnosis or come up with the best possible treatment plan without physically examining the animal. Based on this examination and discussion I can then make recommendations and discuss options with the owner.

Once a good history and clinical exam is performed, some respiratory cases are reasonably simple to diagnose and a treatment plan can be made. This may involve a few subtle husbandry changes and dispensing a course of medications, antibiotics for example. I imagine many hobbyists who have experienced R.I’s in their pet reptiles have undergone a similar process at their vets. Very often this approach is satisfactory and a successful outcome is reached. But there are various pitfalls that may hinder such an outcome, and communication between the owner and vet as well as the knowledge and experience of the vet in question is vitally important at this stage. I will discuss the subtleties and decision making process on appropriate treatments later in this article. If the case is not a straightforward diagnosis based on history and physical examination then further tests may be required. These tests cost money, but are optional. Refusing these tests may alter the likelihood of success. As a vet it is my responsibility to offer them and explain their benefits. As a client it is your responsibility at the initial consult to discuss concerns about costs, ask for alternatives if available and ask questions of your vet as to the value of suggested diagnostics. If finances are limited, I would like to know this at the outset so I can come up with the best possible plan with the resources I have available.

In terms of diagnostics for respiratory disease, perhaps the most valuable is imaging by X-ray to visualise the lower respiratory tract, namely the trachea and lungs. The upper respiratory tract consists of fine bones of the nasal chambers and delicate structures in the throat, so is more difficult to interpret by X-ray but this can still give valuable information particularly where local inflammation, bone infections, tumours or foreign bodies are suspected. X-rays also allow the clinician to visualise the extent and location of disease which determines how aggressive the treatment required as well as allowing a better understanding of prognosis for success. In longstanding or advanced R.I.’s I am often met with reluctance or refusal to allow X-rays by the client, often for cost reasons. Despite warning that treating ‘blind’ may not yield successful results the client then gives informed consent to a ‘best guess’ treatment plan. It is extremely frustrating as a clinician if the case isn’t resolved, goes to another vet or dies at home resulting in an unhappy client, or an accusation of incompetence. I would urge all hobbyists to communicate and discuss their experiences with vet treatment, but to remember that especially on online forums people may omit their own role in deciding a treatment plan, and lay all the blame on the vet if it fails and they lose their animal. As you can appreciate as a vet I can offer best practice and work my way back according to the resources available, but I won’t advise doing a specific test unless I feel it will be advantageous in getting a successful outcome. X-rays are a classic example of a test that give the clinician valuable information to direct treatment appropriately, but can be difficult to convince an owner of any tangible benefit especially where finances are limited. Sometimes not doing a test sets the treatment up for failure from the very beginning.

Following X-rays, bloodwork and microbiological testing are also valuable tools in making a firm diagnosis and therefore choosing a successful treatment plan. In terms of bloodwork, haematology may reveal elevations in specific white blood cells relating to inflammation or active infection. In chronic cases however infection may be confined locally to lesions in the lungs for example and therefore white blood cell counts may be within normal limits. In such cases systemic treatment may be unnecessary and targeted treatments at the lesions of concern may be a more appropriate treatment option. Such targeted options include nebulisation of drugs into the airway directly, or surgical debridement and establishing access to lung abscesses to treat infected tissue directly. Biochemistry values may indicate that the animal in question has other metabolic problems or is heading towards liver or kidney failure due to advanced systemic infection for example. In such a case the value of doing blood tests first is obvious.

Where microbial sampling is concerned in the case of infectious disease there are two main techniques used, lung washes and direct sampling. Lung washes can provide useful information on what pathogen is involved in a specific infection, and subsequently by culturing these pathogens we can ascertain what antimicrobial drugs (e.g. antibiotics) are most effective to treat the infection present. However, it can be difficult to obtain a representative sample using this technique. Several times I have performed tracheal and lung washes in snakes in particular, introducing sterile saline into the airway and aspirating it back out again to sample the cells and potential pathogens causing illness, only to receive a report back from the laboratory stating that no micro-organisms were cultured even though bloods and clinical signs indicate an R.I. Similarly the sample may contain few if any cells when examined under the microscope, so this is a difficult technique and doesn’t always yield the desired results. The second approach is direct sampling of lesions in the lungs or lower airway by using a rigid endoscope or in the case of chelonians drilling a hole through the shell to gain access to the lungs in an advanced pneumonia case for example. If a valuable sample is obtained indicating an infectious agent, it is cultured in the lab and the pathogens causing infection can be identified and tested in order to determine what antibiotic medication would be most appropriate for treatment. In an ideal world, I would use culture and sensitivity for every infection I encounter in clinical practice, on exotic and companion animal cases. This approach is not practical, financially feasible for many clients or arguably necessary in the majority of presentations, as with experience and background knowledge most vets will know the common pathogens responsible for certain conditions, and typically what classes of antibiotics are most suitable for treating such infections. There are always going to be resistant infections or atypical pathogens which require further investigation and possibly an alteration in treatment. So, as you can appreciate even with owner consent to do diagnostics like culture and sensitivity testing in order to chose the right antibiotic for the infection present, the procedures in themselves can present a challenge to the most experienced clinician.

In many respiratory cases, and reptiles that are ‘generally unwell’ with vague signs of illness I will often ask for a faecal sample to screen for parasites, particularly where there is a history of a new animal, wild caught individual, a large collection with several cases of illness, lack of adequate quarantine or failure of initial treatment. As standard, I perform a direct faecal smear and a flotation test which will detect protozoal infections, pinworm, roundworm, tapeworm and lungworm eggs in the majority of cases. Lungworm infections are less common in captive reptiles than bacterial R.I’.s, at least in the UK where I practice but I would always bear them in mind if an assumed bacterial R.I. was unresponsive to best choice antibiotics. In wild caught animals, before I commence any treatment I insist on a faecal screen as they invariably harbour parasitic infection which may compromise an already stressed or debilitated reptile, if not cause the primary illness itself.

Endoscopy can be useful for visualising the airway and sampling especially in chelonians and lizards, but due to the elongated lung in snakes it is less useful. Specialised small rigid endoscopes are mostly required unless in very large reptile patients, and such equipment is very expensive so is not available at every vet clinic, exotic or otherwise.

Using the above diagnostic tools and techniques, a diagnosis can be reached in the majority of cases. However there will always be cases which do not typically present, or are less clear and can be a diagnostic challenge for even the most experienced clinician. Take it from me that these cases are just as frustrating to the vet as the owner. Please discuss your concerns with your vet if you do not understand any part of the treatment/diagnostic process, or if you have suggestions on how to improve treatment again you should talk to them. You are at any point welcome to seek a second opinion or ask for a referral appointment if you think your vet is not managing the case effectively or does not have enough knowledge or experience with the species in question. On a side note this is the reason I always recommend locating a trusted and recommended exotics/reptile veterinarian to treat your animals before the need arises in the first place.

Prevention and Treatment:

Husbandry is arguably the most important factor both in the incidence of respiratory disease in the first place as well as the outcome of clinical case management. An absolutely critical consideration is that the reptile is kept in its preferred optimal temperature zone (POTZ) at all times but even more crucially during treatment. It is pointless administering antibiotics or indeed other medications if the animal is housed incorrectly. Poor husbandry, specifically low temperatures or inappropriate humidity levels for the species in question are the critical factors that predispose to respiratory disease. The animal must have a temperature gradient to control its body temperature. Often reptiles with respiratory disease will seek out the cooler end of their enclosure to slow their metabolism and relieve the demands for oxygen placed on a compromised respiratory tract. This tendency can be counterproductive to successful treatment however in that a slow metabolism will also impair the immune system and the action of the medication will be reduced, so it is important that the coolest area of the vivarium is still well within the POTZ. The warmest end of the vivarium can actually be a little higher than usual but not too far outside the POTZ. Accurate control of heating with a reliable thermostat is vital to prevent overheating the vivarium. One of the common misconceptions relating to R.I’s in reptiles is that boosting the temperatures up high will often resolve the infection itself. Certainly in some instances where there is a low grade infection in a relatively healthy and robust animal this may help and contribute to the animal clearing the infection, but I would question whether the animal may have cleared such an infection of its own accord anyway despite bumping the temperatures up by a few degrees. My advice in such cases is firstly to accurately measure the temperatures in the enclosure, then accurately control the temperatures. These processes require investment of buying a reliable thermometer and thermostat if not already used, which are arguably essential kit in the first place. Many reptile owners presenting their very ill pet to me have no idea what temperature their vivarium is at different times of day or night, and in some cases no idea what temperature their animal needs to begin with, instead trusting that the equipment sold in the pet shop will produce the exact requirements needed for their pet.

In terms of heating equipment itself, the vital parameter for provision of an appropriate POTZ is ambient air temperature. For this reason and of course there are some species-specific exceptions, I prefer and advocate the use of heat lamps, bulbs or ceramic heaters as a primary heat source rather than heat mats. The first reason is that these provide a far more reliable temperature gradient in the ambient air temperature of the enclosure as opposed to a warm spot on the floor or wall of the vivarium provided by the heat mat. Perhaps more importantly, the use of heat mats encourages the animal to either sit on the mat itself if seeking warmth or avoid it entirely and chill to below its POTZ which does not help treatment, in terms of immune function or drug metabolism both of which are intrinsically temperature dependent. The other major problem with heat mat use as the primary heat source is that this system does not encourage the animal to move about its enclosure or maintain activity along a more natural ambient temperature gradient. The effect of providing belly heat only to an R.I. case is that respiratory secretions and infectious material accumulates to a greater extent in static animals sitting on belly heat than in those encouraged to move about more with the provision of adequate space, varied cage furnishings allowing movement in the horizontal and vertical planes as well as sufficient ambient heat to remain comfortable and regulate temperature throughout the entire enclosure as opposed to just in the immediate vicinity of a heat mat.

Thinking of these considerations, perhaps the worst possible husbandry system for R.I.’s in reptiles is the all too common trend of keeping snakes (single lung, poor clearance) in rack systems, with very little space to move (inhibits respiratory clearance), in close proximity to dozens or some cases hundreds of other animals (thus facilitating spread of infectious agents) and where they are not checked frequently enough or for a sufficient time to spot the early signs of infection in the first place. Many large scale hobbyists and breeders, private and commercial alike are the worst affected in terms of R.I.’s. This is no coincidence. As a herpetoculturist for many years myself, my belief was always that if we are to keep such animals we should strive to provide as natural a captive environment as possible for them to keep them healthy. The practice of keeping snakes in particular in tiny plastic tubs without appropriate light and often inadequate heating with no thermal gradient is about as far removed from natural as one can get. Perhaps controversially, I would suggest that if we want to keep and raise healthy animals we as responsible herpetoculturists need to redirect the hobby away from large scale reptile production of highly valuable, in some cases highly inbred genetic mutants kept in entirely inappropriate conditions to maintain long term health, the current royal python craze being a prime example. I appreciate this is idealistic as where there is money to be made economics dictate that minimum animal welfare standards are maintained. But just because everybody else is doing it or this system is now seen as standard doesn’t make it right. In short, if you provide adequate space and appropriate conditions for your few select reptile pets rather than substandard conditions for your large collection, it is likely you will avoid causing respiratory illness notwithstanding accidental introductions of infectious agents in new animals. Quarantine and biosecurity measures are vital in preventing infectious disease entering a collection in the first place, as well as spreading between animals from affected individuals.

For the reasons outlined above, part of my treatment plan involving a respiratory case will always involve a review of husbandry particulars for the patient in question. As a vet it is my responsibility to ask these questions and make suggestions on where I see problems. I’m sure some clients feel like I’m accusing them of making their reptile ill or not providing adequate conditions, but most are open to these suggestions and when I assure them that by making these changes the chance of success will be higher they most often do so. My intentions are purely to fill in the blanks if a client has misunderstood or is unaware of all the husbandry requirements for their pet. A very few clients have repeatedly ignored husbandry advice, for example to get their snake out of the RUB (really useful box; perhaps that should be RIB, respiratory infection box) and buy a heat lamp/thermostat in place of the heat mat. One really frustrating case I had was a chronic R.I, unresponsive to treatment and eventually resulted in having to euthanise a pneumonic cornsnake! Cornsnakes as you all know are hardy creatures. Husbandry in this case was poor. They couldn’t tell me the temperature of the vivarium on any of their multiple visits, despite asking repeatedly for this information. None of the owners would listen or accept that this infection may be husbandry related. On the third or fourth occasion they visited and again I asked if they had changed the housing and heating arrangements as recommended I was met with the angry reply that ‘someone on the forums said cornsnakes are fine on heat mats’. Again I explained that a healthy cornsnake may do fine, but an R.I cornsnake will not. It fell on deaf ears. They were very unhappy to return weeks later after missing their follow up appointment with a very poorly snake. The main reason they were unhappy was that my treatment didn’t work and they had ‘wasted all that money’ extending the antibiotics after each visit. Now they had no option but to give up and have the snake euthanised. I felt for them losing their pet, but even if I provided gold standard treatment for this snake for free, I could not convince them to change the snake’s conditions as they had read online what they were doing was perfectly adequate. So the snake was doomed from the start. I’m sure if asked they would have laid all the blame at my feet for their snake dying, and no doubt called me a dreadful vet. They may have even posted their version of events portraying me as such on their online forum of choice. The reason I relate this story is firstly to highlight the danger of believing everything you read online, regarding husbandry in general and treatment of medical conditions by non-medically trained professionals, but also in terms of vet reviews. There are two sides to the consult table. I hope you can appreciate my frustrations in such cases.

In terms of treatment, firstly I will touch briefly on choice of medication. I could write a whole chapter on the use of antibiotics but it is beyond the scope of this article. The medication dispensed is often blamed if the treatment is unsuccessful, hence my earlier comment on ‘Baytril bashing’. The aim of treating a simple R.I. as an example would be to choose an antibiotic that concentrates well in respiratory tissue, is broad spectrum meaning it is effective against a wide variety or organisms, has a well documented success rate in treating the most common infectious micro-organisms found in reptile R.I’s, has low incidence of resistance, has few side effects and is licensed for use in these species. Baytril, the generic name for the drug Enrofloxacin, ticks all of these boxes believe it or not. As such it is a perfectly good choice in first line antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated R.I’s in reptiles, with several exceptions and some specific considerations. This is why it is often used as a first line drug of choice for a wide variety of infectious conditions in reptiles. It is not necessarily because the vet in question doesn’t know what else to use, but moreso a licensing issue and the fact that it is a very useful antibiotic. I am not familiar with US laws and licensing, but in the UK Baytril is the only antibiotic licensed for use in most exotic species, and there are legal guidelines about using other drugs off-license where necessary. Again these issues are beyond the scope of the article, but because of this many vets will use Baytril as their first choice in reptiles, and change antibiotics later if ineffective. However, Baytril like any drug can be used irresponsibly or ineffectively.

Antibiotics that I frequently consider and use for treatment of R.I.’s in reptiles are the fluoroquinolones Enrofloxacin (Baytril) and Marbofloxacin (Marbocyl), the third generation cephalosporins Ceftazidime (Fortum), Ceftiofur (Excenel) and Cefotaxime (Claforan), the aminoglycoside antibiotic Amikacin (Amikin) and in certain circumstances the macrolides Azithromycin and Clarithromycin or tetracyclines such as Doxycycline. As you can appreciate there is a wide choice available each with it’s own indications and side effects, but unnecessary or inappropriate use of antibiotics can be just as harmful as choosing the wrong drug initially. Choice of antibiotic depends on culture/sensitivity results if available, safety, owner’s ability to administer such medications and often cost of treatment. There are many variables in the use of such medications which can result in success or failure of treatment. The common complaints I refer to reading about on message boards are often the ‘wrong antibiotic’ or that a vet should have been using a ‘stronger antibiotic’. The wrong antibiotic would be one which does not effectively treat the types of pathogens commonly causing the infection in question. A vet prescribing Baytril for a lizard or snake R.I. with poor results when another snake was prescribed Fortum for an R.I. and had great results does not necessarily constitute choosing the wrong antibiotic. To say so is entirely simplistic and doesn’t take into account a multitude of specific variables and the intricacies of the consult and decision making process outlined previously. Similarly, an antibiotic can only be described as ‘not strong enough’ if the vet has prescribed or owner administered an insufficient quantity of the antibiotic. One antibiotic class or drug is not stronger than other medications. They work in different ways and have different spectrum of activity against certain types of organisms. The strength of an antibiotic is dose related, and it is entirely possible that failure of a case may lie in the fact that a low dose was given which failed to overcome the infection. Hence my frustration when I read countless vet bashing threads about choosing the wrong antibiotic or it not being strong enough without any appreciation for other factors which may have influenced the case.

The duration of treatment is critical for example, so most R.I. cases would require at least 14-21 days of continuous treatment in my view. Very often I will prescribe antibiotics for 4-6 weeks in severe cases. If very mild signs I may reassess the animal after 7-10 days and review the treatment plan if appropriate. Dosage decisions need to reflect the individual animal in question and severity of disease versus a risk based assessment of side effects. A sound knowledge of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and experience in treating similar cases is required in order to balance all of these variables and decide on the correct dosage and duration. I make a point of never communicating dosages for general treatment of conditions online, as all too often I find incorrect interpretations or ‘one fits all’ advice on how to use medications by so called experts. Applying such an approach to treatment of complicated disease processes that vary in many ways between species and individual cases is destined for failure. The route of medication is also important and can influence outcome. Certain medications need to be administered to the animal in a specific way on order to be effective. For example Baytril may be given by mouth (per os/PO) or by intramuscular (IM) injection. Fortum on the other hand is never given by mouth, but rather by IM injection, intravenous (IV) injection or indeed subcutaneous (SC) injection. The route the drug is given will affect speed of uptake or absorption as well as duration of action and all of these factors are taken into consideration when dispensing such medications. The owner’s willingness and capability in administering injections if required for extended treatment at home often influences the choice of medication dispensed also. The species in question may determine what route to use also. Anyone who has tried to orally dose turtles and tortoises will tell you it is often not an easy task so this route may be avoided in order to ensure owner compliance with medicating their animal. The oral route in lizards however is much easier, so is often preferred over repeated, painful injections which the owner may struggle performing and which are not without risk especially in smaller species. The oral route in snakes is controversial and several studies have demonstrated that it is not entirely effective in many cases. This is due to the unique nature of the digestive tract in snakes that remains in a quiescent state for long periods between meals and therefore does not absorb medications as effectively or predictably as in lizards and chelonians for example that are designed to eat continuously on an almost daily basis. Therefore in snakes I invariably prescribe injectable antibiotics and teach the owners how to do this safely and effectively at home, or hospitalise the patient if this is not practical. A word on injecting Baytril is prudent at this stage. This is an alkaline drug and does cause some pain/discomfort on intramuscular injection, so in snakes in particular where the oral route is least preferable, I will often use Fortum or Amikin injections as a first choice if necessary. For lizards with an R.I., I will invariably use Baytril by mouth as my first choice, unless culture/sensitivity results tell me otherwise. Finally the frequency of dosing is dependent on the drug and dose chosen and can vary. Whatever drug, dose route, frequency and duration of treatment are prescribed, it is vital to stick to this and finish the course. If you have researched and found evidence or material to the contrary to what has been dispensed for your animal, ask your vet about this before deciding to change the treatment. I would also urge you to attend follow up appointments as requested, even if you think your animal is better.

Supportive care is critical in treatment of any ill reptile, and in severe cases I will often hospitalise the animal in controlled conditions particularly when starting treatment. Correction of dehydration is one of the first concerns for many patients. If the animal is anorexic I may tube feed using proprietary convalescent diets appropriate to the species in question. In some cases I will place an oesophagostomy tube which allows syringe feeding through a tube in the side of the neck directly into the stomach without stressing the animal in question. This is a particularly useful tool in anorexic debilitated tortoises. In delicate or stress-prone species such as chameleons, sometimes hospitalisation can be counterproductive. Each case is judged individually, and according to the owners comfort and ability to treat at home. Nutritional deficiencies may be corrected by multivitamin and mineral injections or supplementation. Hospitalisation also allows daily nebulisation in certain cases, particularly useful in chronic or deep-seated pneumonia cases. Nebulisation is a useful tool which can be used in both the hospital and home environment and involves vapourising anti-microbial drugs and exposing the ill reptile to this vapour in an enclosed chamber to inhale the drug and therefore achieve better penetration of the airway then by systemic treatment alone. Lung tissue penetration by systemic drugs can be difficult for various reasons. The blood-air barrier in reptile lungs is thicker than that of mammals, as well as the tendency in these species to form solid caseous (cheese-like) pus or infectious discharge deep within the lung tissue, rendering the infected areas almost impenetrable by blood-borne drugs. A number of antibiotics can be used for nebulisation including Amikacin, Gentamicin, and Enrofloxacin (Baytril) amongst others. The disinfectant product F10 which is bactericidal, viricidal and fungicidal has been demonstrated to be an effective agent for nebulisation in R.I. cases, although care must be taken to use the correct product and concentration according to manufacturer guidelines. This agent can also be used for nasal flushing in cases of upper airway disease with excessive nasal discharge or secretions. Depending on the case nebulisation may be carried out 1-2 times daily for a maximum of 20-30 minute sessions. Other drugs that may be nebulised apart from antibiotics and antiseptic-disinfectants include steroids for anti-inflammatory action, bronchodilators such as aminophylline to open the airway prior to nebulisation with other agents and finally mucolytic drugs to reduce the viscosity of respiratory secretions. Intrapneumonic therapy is even more aggressive and involves direct administration of drugs into affected lung tissue using endoscopy in the airway or gaining access via an indwelling catheter to the site of lung lesions. This is generally carried out on tortoises under sedation or general anaesthesia, locating the exact location of lung lesions by X-ray or ultrasound and drilling through the carapace.

If parasitic infection is responsible for respiratory disease, then treatment is directed at killing the parasites and preventing re-infection, as well as minimising the side effects of treatment. Nematode infections are generally treated with a number of anti-parasitic drugs including Fenbendazole, Albendazole and Ivermectin. Ivermectin must NEVER be used in chelonians as it is toxic and can cause fatal side effects. Anecdotal evidence for adverse effects of this drug in chameleons also exists so for this reason I generally avoid it in these species. In severe parasitic infections treatment itself can cause further problems especially where migrating larvae ore killed in-situ and subsequent inflammatory processes surrounding the dead parasites can cause more severe clinical signs than the parasitic infection itself. Viral infections can be difficult to treat and often rely on supportive care and prevention of secondary infection, in an effort to allow the animal to clear the infection if possible using its own immune defences. Some anti-viral agents are available, but their use in reptile patients is not widely researched and they are also often cost-prohibitive in general practice. Anti-fungal agents such as ketoconazole and itraconazole can be used to treat fungal disease but accurate dosage is critically important as side effects can be severe if used incorrectly or if the animal is debilitated to begin with.

As you can appreciate, blanket treatment protocols for respiratory disease are impossible to supply so care must be taken when following such guidance from other hobbyists or information obtained online. Each case has its own intricacies and possible underlying causes that may be missed without appropriate investigation at the diagnostic stage. I also hope I have outlined the difficulties in achieving a cure for respiratory disease in reptiles in some cases despite the best possible treatment. By far the best advice I can give is to ensure husbandry and nutrition of reptiles in your care is ideal, particularly with regard to space, ventilation and heating. Proper biosecurity precautions should be put in place in any large reptile collections, to include strict isolation and quarantine of any new additions for a minimum period of 6-8 weeks, preferably longer. Daily observation goes a long way in determining when a reptile is showing signs of illness, and prompt treatment by an experienced reptile veterinarian is often critical in order to achieve a successful outcome.

[ad_2]

exoticpetvetblog

2015-12-30 15:28:24

Source :https://exoticpetvetblog.wordpress.com/2015/12/30/respiratory-conditions-in-reptiles/